The Master of the Fleshy Ears

(Oyo-Kishi)

Situated at the heart of Yorubaland, the Oyo region emerged, by the mid-19th century, as one of the most prolific and influential centers of sculptural production dedicated to the cult of twins, an essential component of Yoruba religious and metaphysical thought. This geographical area, unparalleled in its artistic density within the ibeji corpus, is notable for having concentrated no fewer than fifteen villages, each home to sculpture workshops of remarkable vitality, both ritually and artistically.

Each production center (and at times each individual master sculptor) developed its own stylistic conventions, shaped by local aesthetic logics and differentiated symbolic understandings of the twin figure. Some schools favored elongated forms and intricately carved coiffures, while others emphasized more compact proportions, with pronounced modeling of facial and thoracic features. Far from being purely decorative, these formal decisions played a critical role in the ritual efficacy of the object, conceived as a vessel for àṣẹ, the sacred life force.

Today, ibeji figures from the Oyo region are among the most sought-after examples of historic African sculpture, prized by collectors and museums alike. Their visual power, inseparable from their spiritual resonance, exemplifies the interplay of art and sacred function in Yoruba society.

Among the major production centers in the region, the village of Kishi holds a distinguished place. From the late 19th century through the third quarter of the 20th century, it was home to a workshop whose output—marked by exceptional refinement—far surpassed the average sculptural standard of ibeji figures from the broader Oyo area. At least two sculptors associated with this center have been identified to date. The ensemble of works attributed to this atelier is especially notable for its highly distinctive treatment of the ears: exaggerated in volume and modeled in an unusually fleshy, almost hypertrophic manner. This stylistic hallmark justifies the attribution of the corpus to a single artist or school, which we propose to designate by the conventional name “Master of the Fleshy Ears.”

This operational designation—commonly used in African stylistic studies when signed works are absent—enables us to group, based on rigorous formal and iconographic criteria, a coherent body of work characterized by aesthetic unity and technical mastery. It also opens new avenues for understanding the internal dynamics of ibeji sculpture and for mapping the key centers of artistic innovation within Yorubaland.

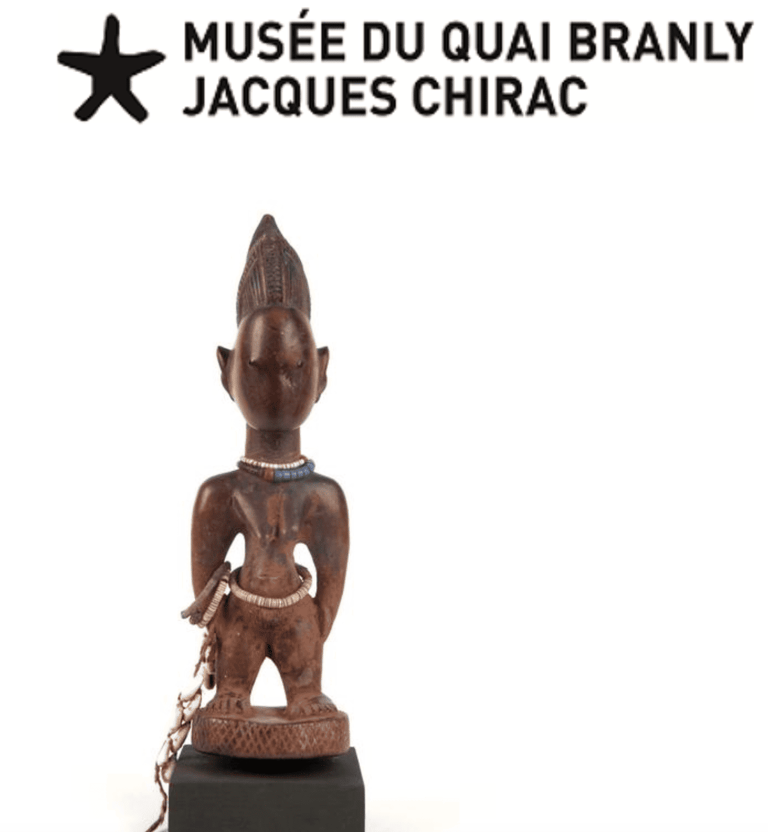

The attribution of a coherent corpus of ibeji figures to the artist conventionally referred to as the “Master of the Fleshy Ears” rests on the identification of stylistic markers of striking singularity within the broader sculptural production of the Yorubaland, and more specifically, the village of Kishi. This sculptor’s hand is most readily recognizable through the highly unusual treatment of the ears, which exhibit a distinctive hypertrophy. These ears, markedly detached from the plane of the face and rendered with considerable volume, appear exaggerated—yet they retain proportional harmony with the rest of the head, suggesting deliberate artistic intention rather than naïve distortion.

A second defining trait lies in the modeling of the mouth, particularly the upper lip, which is consistently sculpted at nearly twice the volume of the lower lip. This hypertrophied labial structure lends the figures a distinctive expression, often likened to a pout or a grimace, and imparts a subtly simian character to the faces—an effect without parallel among other ibeji figures produced in Kishi. This characteristic grants the corpus a unique expressive power, wherein the face becomes the primary locus of aesthetic and perhaps symbolic articulation.

The coiffures across the body of work show a relative homogeneity, divided into two principal types: openwork hairstyles, as seen in the example above, and solid coiffures, such as the one illustrated below. Unlike the greater formal variety found in other stylistic centers within the Oyo region—such as the workshops of Oshogbo or Shaki—the range here remains restrained. Nevertheless, these hairstyles are richly adorned with finely incised geometric motifs, which reflect a high level of decorative sophistication and are particularly esteemed by connoisseurs and collectors for their clarity and visual impact.

Anatomical features, particularly the torso and genitalia, are treated with marked restraint. The breasts are small and pointed, while male genitals are minimally rendered—reduced to their most basic expression, verging on abstraction. This formal economy appears intentional, consistent with a broader aesthetic strategy that emphasizes the head and coiffure as primary vectors of identity and presence.

Lastly, one observes the recurrent use of a crosshatched motif carved into the base of all ibeji figures attributed to this workshop. While this design element is indeed a consistent feature, it cannot be considered a unique identifier of the Master of the Fleshy Ears, as it appears more broadly in works by other sculptors active in Kishi. Rather, it should be interpreted as a localized workshop convention—an artisan signature of the broader sculptural tradition within the village.

The attribution of a coherent body of work to the anonymous figure conventionally referred to as the Master of the Fleshy Ears represents a significant advancement in the stylistic analysis of ibeji figures produced in the village of Kishi, within the broader Oyo region. Through the formal singularity of his sculptural choices, most notably the hypertrophied, deliberately protruding ears, the expressive modeling of the lips, and the richly adorned geometric coiffures, this workshop reveals a consistent and distinctive aesthetic identity whose expressive force far exceeds the normative standards of ibeji production.

Beyond their visual power, these works reflect a deep understanding of the ibeji’s ritual function as a medium of spiritual presence and a conduit between the living and the twin entity. The Master of the Fleshy Ears thus positions himself within a living tradition, while simultaneously asserting a unique sculptural sensibility that is immediately recognizable. His contribution enriches the evolving cartography of major stylistic centers in Yorubaland and underscores the extent to which individual artistic expression, far from being absent in traditional African art, can assert itself forcefully within systems shaped by collective norms.

Below is an example of an Ibeji by the Master of the Fleshy Ears presented at the Musée du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac and another by a follower or apprentice very close to the style of the Master of the Fleshy Ears